From Systems-of-Systems to Capabilities-of-Capabilities

BLUF: Systems engineering built the tools. Capabilities win the outcomes. Decision Intelligence orchestrates both.

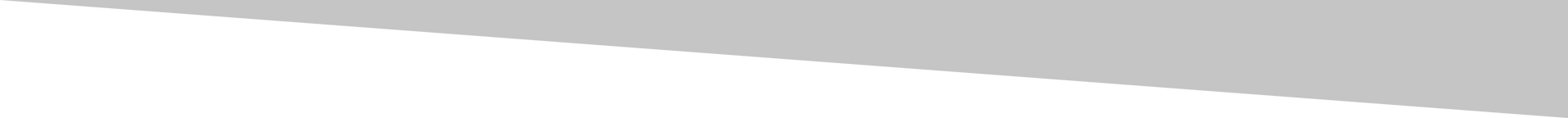

From System to Capability (Image by J Eselgroth w/Gen AI)

The Integration Trap

Systems engineering changed how we build complex things. It gave us architecture, modularity, and integration discipline. It helped us land spacecraft and connect global networks. But it also created a blind spot.

We became so focused on systems we forgot what they exist to produce.

Programs fail not because systems break. They fail because no one asked whether the system could actually deliver an outcome. A fighter jet without pilots, maintenance crews, fuel logistics, and training pipelines is not a capability. It is an expensive artifact.

The GAO has tracked this pattern for decades. In its 2025 assessment, the agency reported that major defense acquisition programs now take almost 12 years from start to deliver even an initial capability. DOD plans to invest $2.4 trillion across 106 of its costliest programs. Most pass every systems engineering gate. They still fail to deliver operational capability on time.

This pattern extends beyond defense. Seventy percent of digital transformation initiatives fail to meet their objectives. According to a RAND study, 80 percent of AI projects fail. BCG researchers found success depends 70 percent on people and ways of working. Only 30 percent depends on technology.

The problem is not bad engineering. The problem is scoping the wrong unit.

Capability Is the True Delivery Unit

A capability is the practical ability to achieve a defined outcome under real constraints. It emerges from the coordinated use of equipment, people, training, and supporting elements. Systems are tools. Capability is what those tools make possible.

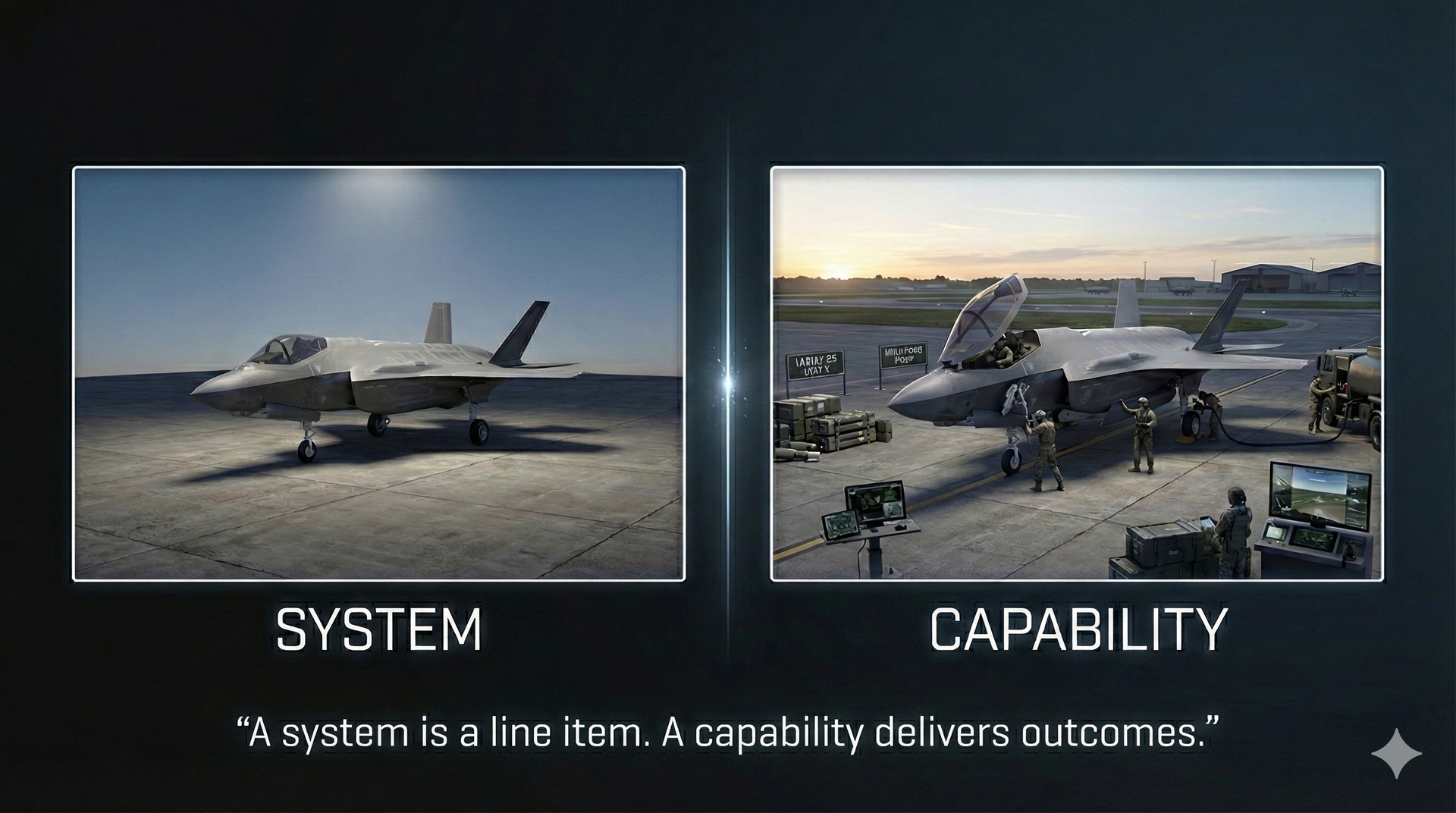

Think about an F-16 and F-35. They are not just two aircraft. They represent two points on a capability axis. Each requires different pilots, different maintenance, different doctrine, and different logistics. The aircraft alone delivers nothing. Capability emerges when the system combines with trained operators and support.

The same logic applies to a pistol and a sniper rifle. The weapon matters. The shooter matters more. A trained sniper with the right rifle, range data, and spotting support produces precision engagement. A novice with the same rifle produces nothing useful.

Example Capabilities (Image by J Eselgroth w/Gen AI)

Consider a data scientist. The capability is not the analytics platform. It is a trained analyst, clean data pipelines, governed data sources, compute infrastructure, and business context working together. The outcome is actionable insight. The platform alone produces dashboards no one trusts.

Or consider an accountant. The capability is not the ERP system. It is a credentialed professional, documented processes, internal controls, reporting standards, and audit trails. The outcome is reliable financial statements. The software alone produces numbers without integrity.

Organizations do not field systems. They field capabilities.

Why Systems-of-Systems Falls Short

Systems-of-systems thinking improved technical composition. It enabled interoperability and modular design. These are genuine advances. But the model remains anchored in technical artifacts.

Real delivery depends on more than artifacts. It depends on people who know how to operate them. It depends on training pipelines producing those people. It depends on consumables arriving where they are needed. It depends on doctrine guiding employment. It depends on leadership making sound decisions under uncertainty.

None of these elements live inside a systems architecture. They live around it. Systems-of-systems thinking does not have a place for them.

This is the blind spot. Programs optimize the technical layer. They underinvest in the human and organizational layers. Then leaders wonder why fielded systems fail to produce outcomes.

Capabilities-of-Capabilities as the Reframe

Shifting to a capabilities-of-capabilities lens changes everything. The unit of analysis becomes outcome-generating capacity. The question becomes "what can we achieve?" not "what can we integrate?"

This reframe treats capabilities as composable, measurable, and improvable. A mission outcome often requires multiple capabilities acting in concert. Air superiority requires strike, surveillance, refueling, and command capabilities working together. Each one depends on systems, people, training, and logistics.

Composing capabilities is a decision problem. Prioritizing them is a decision problem. Sequencing investments across them is a decision problem. This is where decision intelligence enters the picture.

Leaders operating at this level ask different questions. What capability am I buying? What capability am I retiring? What capability gap creates the most risk? These questions drive smarter investments than "what system do we need?"

Implications for Leaders

Adopting a capability lens changes procurement, planning, and measurement. Procurement shifts from buying systems to buying outcome-generating capacity. Planning shifts from integration schedules to readiness timelines. Measurement shifts from technical milestones to operational effectiveness.

This is not a rejection of systems engineering. It is an elevation. Systems engineering remains essential for building the tools. Capability thinking ensures those tools produce outcomes.

The leaders who grasp this distinction will outperform those who do not. They will spend less chasing systems that never deliver. They will invest more in the people, training, and logistics enabling real capability.

The Takeaway

Stop asking what system you need and start asking what capability you are building.

Sources:

- GAO-25-107569, "Weapon Systems Annual Assessment," June 2025

- Gartner/BCG analysis on digital transformation failure rates, 2025

- RAND Corporation / SHRM, "Prioritize Human Factors: The Hidden Key to AI Project Success," October 2024